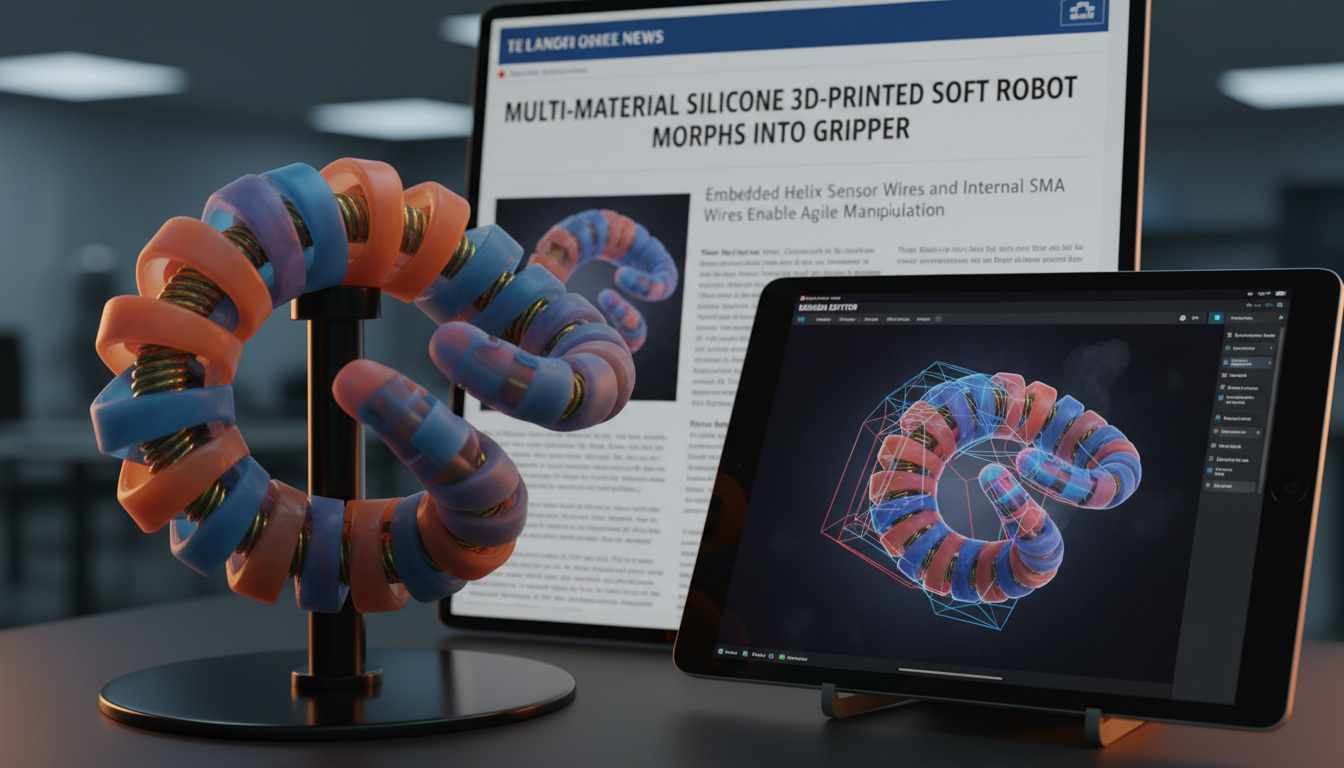

FluxLab: Designing 3D-Printable Shape-Changing Devices with Embedded Sensing

Additive manufacturing is moving beyond static parts toward systems that can sense, adapt, and reconfigure. FluxLab, a new research toolset published on December 2, 2025, illustrates that transition by combining multi-material 3D printing, embedded actuation, and built-in deformation sensing to produce shape-changing devices ready for practical demonstrations. The work focuses on printable silicone devices that fold, grip, and morph under programmable control, pointing to immediate uses in soft robotics, interactive consumer objects, and adaptive components for constrained spaces.

What is FluxLab?

FluxLab is an integrated design and fabrication pipeline for producing 3D-printable, shape-changing mechanisms with embedded sensing. At its core are three structural innovations: a channel for a shape memory alloy (SMA) actuator, lattice padding to tune local elasticity, and helix surface wires that anchor and guide deformation while also serving as sensing elements. The authors pair these hardware primitives with a design editor tailored to stereolithography printing in silicone resins and an ML-based classifier that maps geometry and actuation inputs to predictable deformation behaviors.

How the system works

The SMA channel carries thin wires that contract when electrically heated, providing compact, high-force actuation inside a soft printed body. Lattice padding is used selectively to soften or stiffen regions, allowing designers to program bending locations and compliance without changing the outer shell. Helix surface wires run along the exterior and act as both structural guides and deformation sensors: their changing geometry under load produces signals the system can read to infer shape and movement.

The design editor lets users place these elements interactively, tune actuation paths and lattice density, and export print-ready files for SLA silicone resins. After printing, users embed the SMA wires and connect the helix sensors to simple readout electronics. The ML classifier, trained on simulated and experimental data, helps predict how a chosen design will deform under particular heating patterns, which reduces the trial-and-error cycle typically associated with active soft devices.

Demonstrations and capabilities

Practical demonstrations reported with FluxLab include a self-deforming clip for steamers, a remotely controlled soft gripper, and an interactive lamp that changes form in response to user input. These examples show the strength of the approach: compact actuation with robust sensing inside a single print, fast iterations enabled by the editor and classifier, and the ability to tune elasticity locally to achieve distinct behaviors from the same base geometry.

Applications and limitations

Near-term applications are clear. Soft robotics benefits from integrated actuation and sensing with minimal assembly. Consumer products such as adaptive wearables, dynamic grips, or novelty devices can leverage single-print fabrication for lower cost and easier customization. In constrained or delicate environments, shape-changing devices that can morph to fit a space or gently grasp fragile objects are particularly promising.

However, several challenges remain. SMAs require careful thermal management and power; repeated cycling impacts lifetime and requires attention for long-term reliability. Embedded sensors in soft materials can suffer from drift, hysteresis, and signal noise, necessitating robust signal processing and calibration. Material compatibility with electronics and connectors is another practical hurdle for producers wanting to scale beyond lab prototypes. Finally, while the ML classifier accelerates design, broader adoption will depend on larger datasets and open libraries of validated primitives.

Why FluxLab matters

FluxLab is important because it demonstrates an executable path from printed prototype to functioning, controllable device without heavy post-fabrication assembly. By combining actuators, tunable compliance, and sensing into one manufacturable flow, it shortens development time and opens up new product categories that exploit shape change as a core capability. The approach also underlines the broader trend in additive manufacturing: moving from objects to systems, where material, geometry, and embedded functionality are co-designed.

For practitioners, FluxLab offers immediate inspiration: consider adaptive seals that tighten on demand, tools that change grip profiles to match parts, or compact fixtures that deploy only when powered. For researchers, it points to fruitful directions in materials that better integrate conductors and sensors into soft matrices, improved actuation technologies that reduce thermal load, and control strategies that combine learned models with simple closed-loop feedback.

If you are curious about reproducing these results or adapting FluxLab ideas to your projects, the paper provides design rules, fabrication notes, and examples that make hands-on experimentation straightforward for anyone with access to a multi-material SLA workflow and basic electronics.

Original title and source: FluxLab: A Toolset for Designing 3D-Printable Shape-Changing Devices with Embedded Deformation Sensing

This page contains affiliate links and I earn a commission if you make a purchase through one of the links, at no cost to you. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.